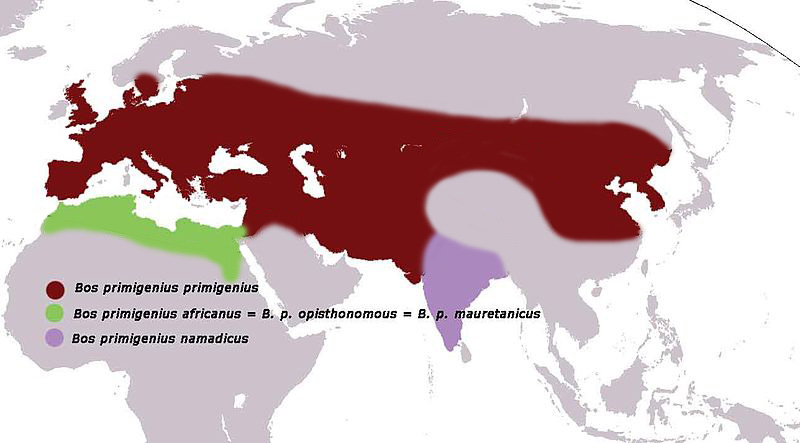

The classic convention is that there are three subspecies of aurochs – Bos primigenius primigenius, the European one, Bos primigenius namadicus, the Indian one and Bos primigenius africanus, the African one. Here is a chart for the distribution of the subspecies:

As you see, material from Central and East Asia are included in the European subspecies primigenius. In western literature, the East Asian aurochs material is described as very similar to that of Europe (van Vuure, 2005).

However, there is Asian literature that is barely recognized in the western scientific community that assigns the material to its own subspecies, Bos primigenius suxianensis [1]. A 2018 study found that aurochs remains were pretty abundant in Neolithic China, and that much of the material has been wrongly assigned to Bison previously. It was also found that East Asian aurochs belonged to a unique haplotype (haplotype C) and therefore were genetically distinct from other aurochs populations [2]. Chinese aurochs were probably hunted, and most likely also hunted to extinction as were the European populations.

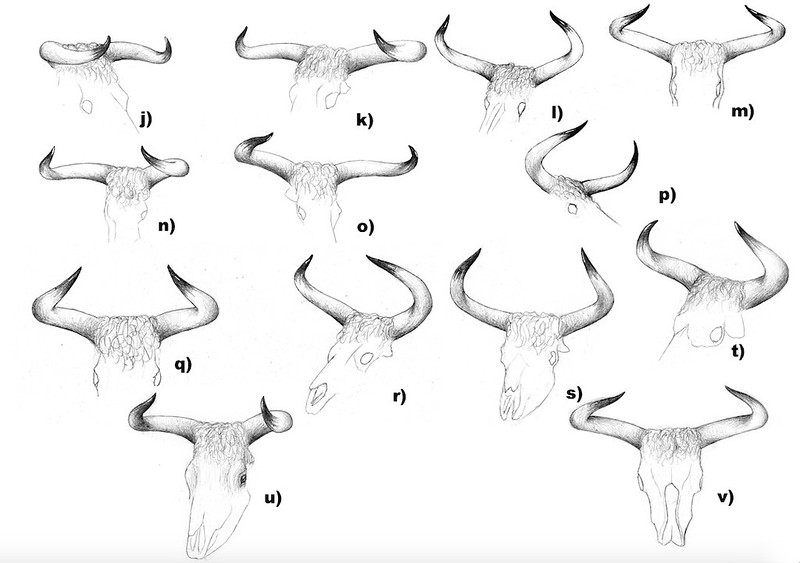

Not only were those East Asian populations genetically distinct, the bone material that is available on the web shows some morphological differences to the European subspecies. The horns are always long and more upright than what is average in the European population, and the shape is slightly different as well. They do not curve inwards that strongly, and they curve more upwards at the base. You see that in this and these specimen. Also, the nasal bones are somewhat raised and more convex than in the European subspecies. You see that in this Chinese specimen and the Baikal skull.

I did a life reconstruction of the specimen linked above:

Note the different horn shape and the convex snout. Nothing is known about the coat colouration of East Asian aurochs, but for this drawing I assumed it had the same colour as the European subspecies.

So it seems that Central and East Asian aurochs were genetically and also morphologically distinct populations, justifying its subspecies status. Therefore, there actually were four wild aurochs subspecies. The reason why the Asiatic subspecies is not part of the “basic aurochs knowledge” is probably that the Chinese literature is less recognized in the western scientific community, and that the bone material (which even includes nicely preserved complete specimen) is less noticed compared to the plentiful European material, except for the Baikal skull. It would be interesting to know if there was a continuum between primigenius and suxianensis, as the distribution area apparently was continuous at least some of the time of their existence. The Kiev specimen, which is the Easternmost specimen of the European subspecies that I know of, does have some similarities in horn shape.

The aurochs apparently was a species with a wide geographical range and regional variations. The European subspecies which is the “standard” when we think of an aurochs, the African subspecies that apparently had a colour saddle, the Indian aurochs with its slender cranium and the long wide-ranging horns, and the East Asian aurochs with the slightly different horns and the convex snout. When we look at other bovines with a wide geographical range such as the Banteng or the Cape buffalo, there might have been more local colour variants that we do not know of.

Literature

[1] Xie: A skull of Bos primigenius suxianensis from Anhui. 1988.

[2] Cai et al.: Ancient DNA reveals evidence of abundant aurochs (Bos primigenius) in Neolithic Northeast China. 2018.