Genetic studies have helped a great deal to understand the history of domestic cattle populations in recent years.

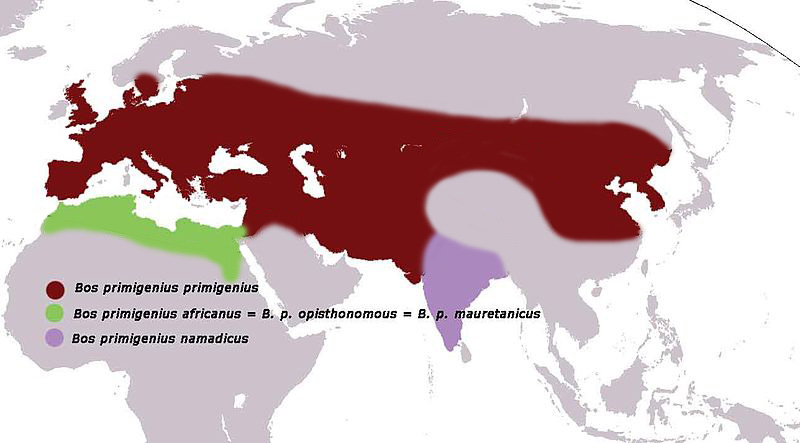

For example, it has been resolved that many Southern European cattle breeds have influence from North African taurine cattle [1], which is not surprising considering that there were trade routes in ancient times. North African taurine cattle are genetically distinct from other taurine cattle, which is interpreted as the result of significant introgression of African aurochs [1]. Therefore, many Iberian and some Italian breeds might have African aurochs in their ancestry. For Chianina (and related breeds such as Romagnola, Marchigiana and others) in particular, zebuine influence has been detected as well [1]. This does not surprise me that much, as I have been suspecting that the white colour of Chianina (produced by at least two different alleles, on the Agouti and Dun locus) is actually inherited from zebus. Some zebu breeds have exactly the same white colour as Chianina, for example see the Nelore breed. Also, the face of Chianina looks slightly zebuine to me, as well as the fact that it lacks curly hair on the front head (which is typical for zebuine cattle but rare in taurine cattle).

So Chianina is influenced by zebuine cattle. This might be used as an argument against the use of Chianina in "breeding-back" by those who want to use Maremmana instead for large size. However, Podolian cattle - such as Maremmana - are significantly influenced by zebuine cattle as well [2,3]. This also shows in the phenotype: I suspect that the upright horns, large dewlap and Agouti dilution of Podolian cattle are derived from zebuine cattle.

But I think this is neither an argument against Chianina or Maremmana. Zebuine influence is simply not all that uncommon in taurine cattle, and unavoidable for "breeding-back", as many breeds needed for certain traits, such as size, have zebuine influence.

As an interesting side note, it has been recognized that zebus share some wildtype alleles with the British aurochs whose genome was fully sequenced, while taurine cattle have other alleles on these loci [4]. So zebus do have some alleles in common with the European aurochs.

[1] Decker et al.: Worldwide patterns of ancestry, divergence and admixture in domestic cattle. 2014.

[2] Papachristou et al.: Genomic diversity and population structure of the indigenous Greek and Cypriot cattle. 2020.

[3] Upadhyay et al.: Genetic origin, admixture and population history of aurochs (Bos primigenius) and primitive European cattle.

[4] Orlando et al.: The first aurochs genome reveals the breeding history of British and European cattle. 2015.