The modern Przewalski’s horse has a comparably uniform coat colour: a bay dun base colour often with a reddish tone, combined with the prominent countershading and white muzzle (pangare). This has become the standard colour scheme for wild horses. There is some variation, some individuals are more reddish than others, some are more lightly beige in colour, but apart from that, current Przewalski’s horses do not vary greatly in colour.

However, what we see in modern Przewalski’s horses is the result of the genetic bottleneck due to the population crash in the 20th century. Photos and descriptions of individuals prior to the genetic bottleneck event from the late 19th century and early 20th century show that originally there was much more variation in the coat colour of the Przewalski’s horse than what is the case now, also including colour alleles that have disappeared from the modern population.

There were both very dark and also very lightly coloured individuals in the herds. They were not geographically separated but from the same populations and were often sold together [1]. An example for such a lightly coloured individual was a stallion caught from the wild and brought to the Haustiergarten Halle, Germany, in 1901 [1]. Some modern Przewalski’s can be more lightly coloured than others even today, but the photos show that some individuals prior to the bottleneck were very light in colour. A famous example for a dark individual is the stallion Waska, which was the first Przewalski’s horse brought to Europe and could be ridden [1] (you find a photo of him on Wikipedia). The photos of this and other dark individuals show that the countershading is slightly reduced, and that the colour is way darker and less shaded than in the modern Przewalski’s horses. I think it is well possible that these dark individuals had the non-dun1 phenotype caused by the d1 allele being present homozygotely on the Dun locus. This allele has been found in a 42.000 years old wild horse and a roughly 4.000 years old horse, both from Siberia [2]. The youngest date for the separation of the Przewalski’s horse’s lineage and that of the domestic horse was 38.000 years ago [3], making it possible that the non-dun1 allele was present in the wild populations before the lineages separated. Another stallion from the early 20th century that was documented in photographs, named Schalun [1], was so dark that I think it is very unlikely that it had the dun dilution. It does not look as if it was the domestic non-dun2 mutation, the colour resembles much that of some Gotland ponies, which were found to have the d1 allele [2]. It is of course possible that Przewalski’s got the d1 allele via introgression from domestic horses but considering that the allele was already present in late Pleistocene wild horses, it is more parsimonious that the dark-coloured Przewalski’s horses were a reflection of the original wildtype diversity in the wild horse, if those individuals indeed had the d1 allele.

Pangare (light ventral countershading with a white muzzle) is typical for wild equines, and all modern Przewalski’s horses have it. However, it was not uncommon that wild-caught Przewalski’s horses completely lacked pangare, f.e. many of the wild horses brought to Askania Nova in the early 20th century [1]. These horses lacking pangare must have had the non-pangare allele Panp. It is certainly possible that this was the result of domestic horse introgression in the wild that undoubtedly took place, but I think it is also plausible that this allele first appeared in wild populations, as some cave paintings show horses that definitely lack pangare. Cave paintings, however, must be taken with caution. Only a genetic test of predomestic wild horse DNA samples could clarify if non-pangare was a wildtype or a domestic allele.

There were also individuals with lightly coloured legs. Usually, in wildtype-coloured horses (be it bay, bay dun, black, black dun) the distal half of the legs is coloured dark to very dark, except for a light area at the back of the leg of varying extent. Apparently in some individuals this light area extended across the entire leg, resulting lightly coloured legs. There is at least one photograph of an individual having such legs [1], and descriptions of wild Przewalski’s from the late 19th century mention lightly coloured legs.

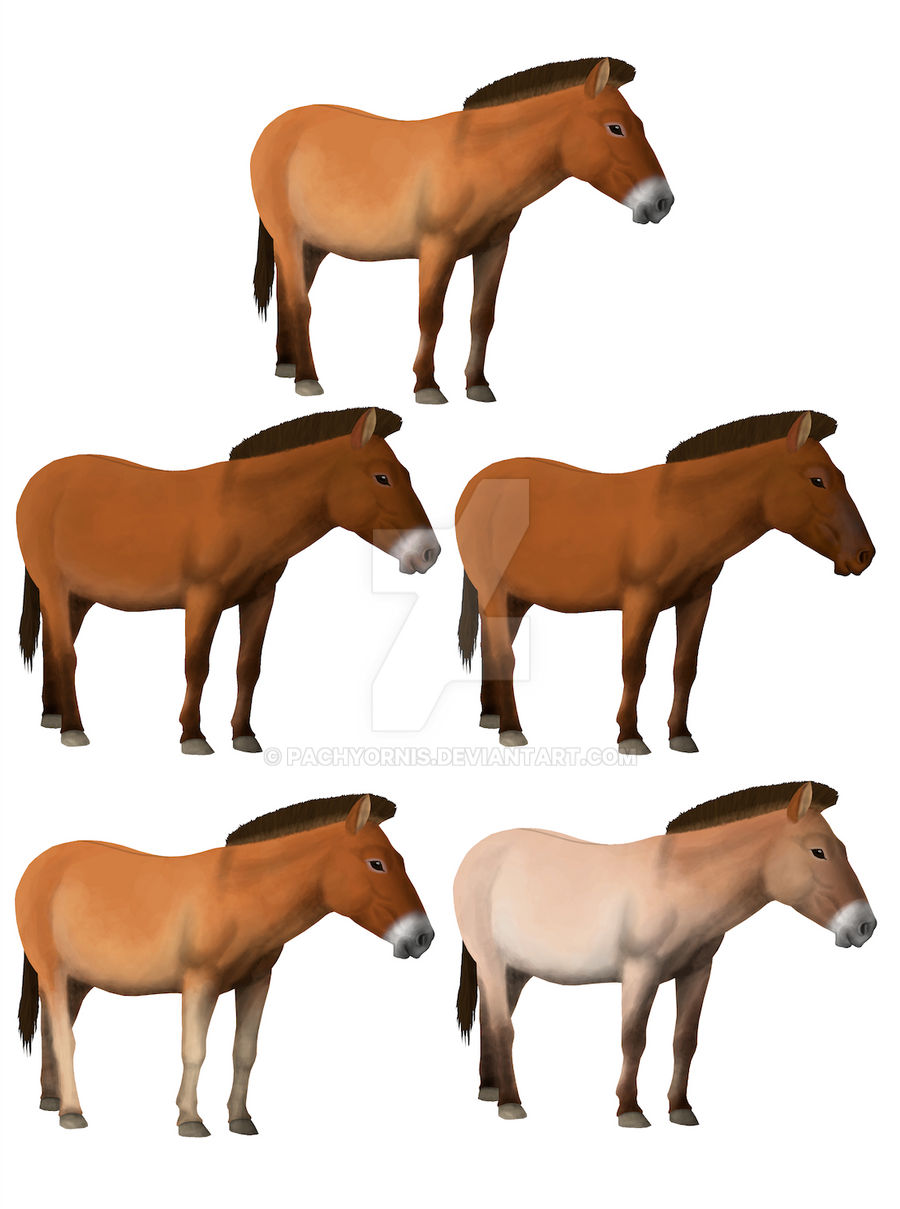

I did an illustration of the original coat colour diversity found in the Przewalski’s horse. It shows, from top to bottom and left to right, the colour type that is now prevailing in the population, the dark variant that is possibly non-dun1, the non-pangare one (I combined it with the dark variant, based on the stallion Schalun, but of course also lighter coloured ones could be non-pangare), the lightly coloured legs, and the very lightly coloured variant. All these illustrations are based on photographs of actual individuals that lived in the early 20th century and often were caught from the wild.

What happened to the colour variants not present in the modern gene pool anymore? One reason for their disappearance was the population crash in the 20th century, which caused a reduction in allelic diversity. Another reason is, in fact, selective breeding. It was very likely the case that the lighter-coloured individuals with pangare and visible leg stripes were preferred in breeding because the responsible breeders thought that a wild horse must look that way [1,4]. This idealization of the Przewalski’s horse appearance caused these colour variants to disappear – there are no non-pangare individuals anymore (EDIT: There are in fact some non-pangare individuals surviving in Mongolian herds at least), and also no very dark, possibly non-dun, but also no very lightly coloured ones [1,4]. I do not think these variants were actively selected against, but apparently nobody paid attention on preserving them in the gene pool, resulting in their disappearance.

The current Przewalski’s horse is not completely free of domestic horse introgression. As a consequence, domestic colour variants occur from time to time. Some herds may have individuals with a white stripe on the face [1], others show a chestnut colour [1,4], what means that the e mutation on the Extension locus has been introduced into the Przewalski’s horse gene pool by interbreeding with domestic horses.

Therefore, while some wildtype colour variants have been lost in the last remaining wild horse, domestic ones have been introduced. This is of course not desirable for maintaining the original wildtype diversity. This could, theoretically, be fixed. For example, herds in which chestnut Przewalski’s have appeared could be tested for the eallele, and those selected out, what, on the other hand, bears the danger of selecting out wildtype diversity that is needed in the limited gene pool. The non-pangare allele could be reintroduced either by gene editing (which would be effortful) or crossing in a non-pangare domestic horse (which would be controversial for good reasons). But it is questionable if single colour alleles are really that important.

EDIT: modern representatives of these colour variants can be seen here.

Literature

[1] Volf, Jiri: Das Urwildpferd. 1996. Neue Brehm-Bücherei.

[2] Imsland et al.: Regulatory mutations in TBX3disrupt asymmetric hair pigmentation that underlies Dun camouflage colour in horses. 2015.

[3] Orlando et al.: Recalibrating Equus evolution using the genome sequence of an early Middle Pleistocene horse. 2013.

[4] Oelke, Hardy: Wildpferde gestern und heute – Wild horses then and now. 2012.

This stallion from Hustai NP seems to lack pangare, no? https://www.fotocommunity.de/photo/przewalski-horse-at-hustai-national-p-wolfgang-ende/42021057

ReplyDeleteInteresting, many thanks! Seems like the non-pangare allele did survive in the Przewalski. Perhaps the authors I was citing were not aware of these because the Mongolian population is less accessible in the west. That one stallion is dark indeed, but not as dark as some of the historic individuals.

DeleteYou're welcome. Another interesting - if less spectacular - individual may be this lightly coloured one with reduced leg markings: https://blog.wwf.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/1920-blog-Przewalski-Pferde-0052594967h-c-IMAGO-Xinhua.jpg

DeleteI'm not sure btw. if you saw my comment on Azrael. As of earliert this year, he still is the Neandertal breeding bull.

Yes, I saw your comment on Azrael, thanks for the info - I am happy that this bull is still there, having Steinberg/Wörth + Neandertal is a very good combination within Heck cattle.

DeleteThe second horse from the left is pretty dark too. And also from Hustai National Park. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:PrezHorseHustai.jpg#mw-jump-to-license

ReplyDeleteErythricism is a very often occuring spontanous mutation in which the black pigment is turned off resulting in a reddish animal. Also in horses you can not pretend it is all reducable to only one such mutation in the past resulting in all red (chestnut) horses coming from that one and only ancestor. So it is very much possible in a closed off and genetic narrow population like prewalski’s horse you get that red-mutation. I do agree about introgression by domestic horses though. ( Peter Donck)

ReplyDeleteThat's certainly possible, but when they occurr in a population where there has been confusion revolving which animals are pure and which not, it is suspicios when some individuals have erythricism like a domestic horse. I wonder which colour the Mongolian domestic mare had that was crossed in.

DeleteThe Mongolian domestic mare was chestnut.

DeleteIs it possible that the non-pangaré trait has been introduced by a domestic horse?

ReplyDeleteYes, as I wrote in the post.

DeleteBut if, the introgression event must have occured in the wild before PH were caught.

DeleteHi Daniel, when I watched an episode of "Anna und die wilden Tiere" with my son yesterday, I had to think back to this post of you. There are at least one relative dark przewalski like that one on the photo from the Wikimedia-Link I annotated above. There is also a very light one from the wild.

ReplyDeletebest regards Hannes

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nfCHOcGkeBQ

Here is a french documentary about the Przewalski Horse with some interesting shots of the dark individuals.

ReplyDeletebest regards

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z0kttAIpYeY