I have

always been fascinated with extinct animals, among dinosaurs especially those

that have been exterminated by man. The thylacine was the hero of my early

childhood. When I rediscovered this subject for me some years ago, and

researched on all the exterminated megafauna around the globe, I inevitably concerned

myself with the aurochs and heard of those “breeding-back” attempts. The idea

fascinated me – selective breeding with living descendants in order to reconstruct

the original wild type and to fill a gap in nature man created. I became almost

obsessed with this idea, so that I always feel I have to explain myself why I engage

myself with the horn shapes of some cows or the coat colour of some horses. It is

true that the whole breeding-back issue is a very narrow niche, but to me it is

connected to a lot of other fields.

Arguing

about the need of reintroducing aurochs-like cattle and primitive horses into their

former range partly depends on the so-called megaherbivore hypothesis which

claims large herbivores through their interaction with the flora more diverse

landscapes than a closed canopy forest or climax biotope would be. I am no

hardliner of that thesis (some of them suggest that Europe would be an open

savannah/grassland with huge herds of herbivores like the African Serengeti) but

I think large herbivores do have an influence on the flora they live in, though

certainly not a larger one than climate, soil parameters and terrain. There is

a lot of literature on this subject to dig in, and it is exciting for me to try

to compose a synthesis of that highly polarized discussion. The megaherbivore

hypothesis itself is connected with the Overkill hypothesis that suggests that

many members of the megafauna that died out towards the end of the last glacial

period or shortly after it are victims of early human hunters. As the theory

outlined above, this is another very controversial and emotionalized subject –

I had been concerning myself with this issue years before I discovered

breeding-back for me, but I won’t discuss it here any further because it is not

really relevant for breeding-back.

I always

want to emphasize that breeding-back is not simply something for fanciers that

want to create the breed of their dreams and keep them on paddock is or in

zoos, but that it is the long-term goal to create an authentic, ecologic

substitute for the extinct archetypes they are bred to resemble. These animals

even now have a practical use in conservation and demonstrate their importance

in their former ecosystems; regardless of how large the impact of

megaherbivores on landscapes really is, they were and are important for a lot

of species in their native biotopes. Many grazing projects in Germany, the

Netherlands and other countries underline that.

|

| © Jeroen Helmer |

Reintroduction of large

herbivores also provide empirical tests for hypotheses like the megaherbivore

hypothesis or the cascade caused by the lack of predators which leads to a high

population density of herbivores and therefore overgrazing, and what that means

for the interaction between herbivores and the biodiversity of flora and fauna.

Breeding-back is a tool of conservation because releasing their results into their

native habitats is the reintroduction of a native species. That is why large

reintroduction initiatives like Rewilding Europe have integrated primitive

cattle and horses into their programmes. Europe’s megafauna without wild cattle

and horses as much as Southern Africa without populations of the Plain’s zebra

simply would not be complete, and breeding-back gives us the chance to fill

that gap in the most satisfying way.

The

breeding process itself requires to have some knowledge on the rules of

inheritance and its relevance for breeding a certain desired phenotype.

Inevitably you get into colour genetics. I also try to find out more about the

difference of qualitative and quantitative features and how to select

efficiently on the latter traits. Furthermore, population genetics are relevant

for breeding-back. If you finally have a herd (or several herds) of animals

with the desired features and start to expand and fragment the population the

genetic composition of the new sub-populations gets changed, and some will have

a higher portion of undesired recessive alleles or variations of any trait than

others, leading to phenotypic more or less diverging herds (genetic drift). Genetics

also are the tool to determinate whether there was local introgression from aurochs

or wild horses into their respective domestic counterparts and how extensive

that introgression was. It also explains why selective breeding just with

related animals that do neither descend from the desired extinct animal nor

contain all the genes in the extinct gene pool will only produce a superficial similarity.

I’m an amateur on genetics but breeding-back certainly increased my knowledge a

lot.

Breeding-back

is closely connected with dedomestication. To me, dedomestication is exciting

because it actually is evolution happening in front of our eyes – yet feral

animals are sadly often considered ecological pests and invasive species by the

majority of biologists (in many ecosystems they certainly are, though) and are

under-studied. Of course the environment influences the condition of the body

of the animals, but the changes observed in domestic animals becoming feral are

certainly also genetic, and in many cases “new old traits” evolve, phenotypic

as much as behavioural. The pleiotrophic effects involved in dedomestication

surprisingly favours features not intuitively thought to be influenced by

natural/sexual selection after only a few generations in the wild; this is

exactly the reversal of what has been observed in the Farm fox experiment,

which aims to study the genetic, phenotypic and behavioural changes caused by

domestication.

|

| Feral hogs in Alabama |

In fact, breeding-back also requires to research on the changes

that wild animals go through while being domesticated to better understand how

a non-dedomesticated breeding-back result will be different from the desired

extinct wild type. Feral cattle and horses are prime models for filling gaps in

our knowledge about the social behaviour and ecology of their wild types, so

that there is a mutual gain of information: the desired archetype tells us what

breeding-back has to focus on, and results of breeding-back living semi-feral

or feral tell us some aspects about the extinct archetypes we otherwise could

never know from the limited data we have.

Furthermore,

breeding-back is also an exciting historical, archaeological and paleontological

puzzle, because doing that work efficiently requires a profound knowledge on

the extinct animals you are focusing on. What did it look like exactly? What do

we know about its behaviour and its ecologic niche? What was its preferred

habitat and its influence on other faunal and floral species? How large was its

total range in a climatically comparable period? What were the causes of its

extinction and the chronology of this process? In order to answer these

questions information obtained from the sources mentioned above have to be put

together properly, and you have to know where to look for and which sources are

trustable and which are not. Many historic references are reproduced only from

second or third hand, leading to confusions and Chinese whispers. The more

information you have, the more complete the picture will get. You constantly

have to reconsider the conclusions you have drawn previously, often leading to

surprises, and pay attention that your view does not turn into a static thought

system and biased view – this would be exactly the opposite of scientific

thinking, and unfortunately sometimes is practised by exactly those who claim

to have the only scientific approach.

|

| Researching on other wild bovines brings you information about the aurochs and vice versa |

The species

that are the goal of breeding-back projects also can serve as models for their

taxonomic group. The Aurochs, Quagga and Tarpan engage me to concern myself

with bovine and equine evolution and phylogeny, and researching on related

species is always very helpful as it might have some implication for reconstructing

the biology of their extinct relatives. The basic anatomy, digestion systems

etc. are roughly the same among perissodactyls and ruminants, so if you learn

about the physiology of cattle and horses you learn about the physiology of a

whole set of species. Furthermore, it is interesting to compare the social

behaviour of the different species. For example, that of each of the wild

bovines (buffaloes excluded) is about the same. What is the purpose of the

exceptional sexual dichromatism displayed by some bovids, which is rather

unusual among mammals? Why do horses and bison not show it? Therefore,

researching on the biology of these very few species gives a clue on the

biology of a lot of mammals in general.

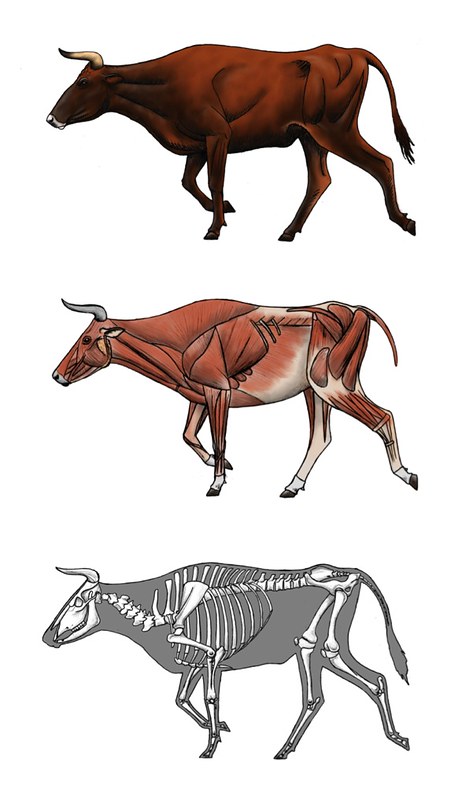

|

| Reconstructing an aurochs cow (Sassenberg specimen). All rights reserved. |

For me as a

self-thought amateur animal artist, the obsession of drawing the one accurate

and satisfying reconstruction of whatever species relevant for breeding-back is

very helpful for improving my artistic skills. As I drew extinct dinosaurs and

other Mesozoic reptiles for many years, I was quite inexperienced when I

started drawing exterminated mammals. Not

only did drawing loads of aurochs increase my knowledge on mammalian

soft-tissue anatomy a lot, it also is incredibly refreshing to shift from

dinosaurs to herbivorous mammals. But art is not only relevant for me.

Qualitative, artistic reconstructions are important for breeding back because

it shows what the breeding has to focus on, and how the animals have to look

like to be satisfying. If you don’t know the appearance of the desired end result,

you cannot select for it.

I've been wondering how much further could the Tamaskan breed be pushed to resemble a wolf more than they already do?

ReplyDeleteI think they pretty much reached the limit of what selective breeding can do, to achieve a greater resemblance real dedomestication would be necessary: release a number of Tamaskan into a reserve with deer and other prey animals and do not interfere. I think they would evolve more wolf-like skulls, larger brain size, more complex social behaviour and whatever else traits that would be re-developed by pleiotropic effects and natural selection. But even then they probably would still not be identical with grey wolves, although very similar. That's the way I see it at least.

DeleteI'd merely like to say that I appreciate your unique contribution to world culture. I'm interested in what you have to share.

ReplyDeleteThank you very much!

Delete